By: Dr. Joel Faidley, CMA

A major challenge for management accountants and manufacturing companies is control of operations and the resulting impact on their financial statements. The causal effects of standard operating procedures, work instructions and shop-floor decisions impact the financial performance of inventory-centric companies. The lifeblood of many companies is inventory, and the dual focus is to maintain sufficient levels of raw materials to produce finished goods for customer expectations and minimize the investment of cash in slow-moving or obsolete inventory. Considerable effort is expended by corporate administration and plant management to drive continuous process improvement through lean principles and reduction of process variation.

A case in point is Exide Technologies’ largest manufacturing plant and distribution center in Bristol, Tennessee. At the peak of the facility’s lead-acid battery manufacturing, production volumes exceeded 30,000 units per day with 1,000 employees. The responsibility and accountability to manage the inventory, production and supply chain for customer orders fell squarely on the shoulders of the plant manager, production manager, controller and materials manager. The site controller is viewed as the one knowledgeable in financial reporting, budgeting and forecasting and as the overall business leader for the facility since their knowledge of the causal effects of shop-floor decisions has significant implications for financial results. The departments of quality assurance, engineering, facilities maintenance, distribution, human resources and environmental health rely on the controller and the accounting department to supply insight into key performance indicators in both dollars and units of measure.

The evolution of basic policies and procedures through adaptation to new and complex reporting requirements was gradual and allowed for thoughtful improvements. The onset of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX),1 specifically Section 404: Management Assessment of Internal Control, dramatically increased the accountability of various processes at the manufacturing plant level. Arguably one of the most complicated and time-consuming sections of the act, the controller and plant manager review and sign off on a large number of controls each quarter called an EICE (Exide Internal Control Environment) checklist. Most of the processes the controller is accountable to check on are asset-related and revolve around inventory and fixed assets. Accounting professionals know the importance of not overstating assets in light of the conservatism principle and the consistency necessary when applying materiality and disclosure principles to operational decisions.

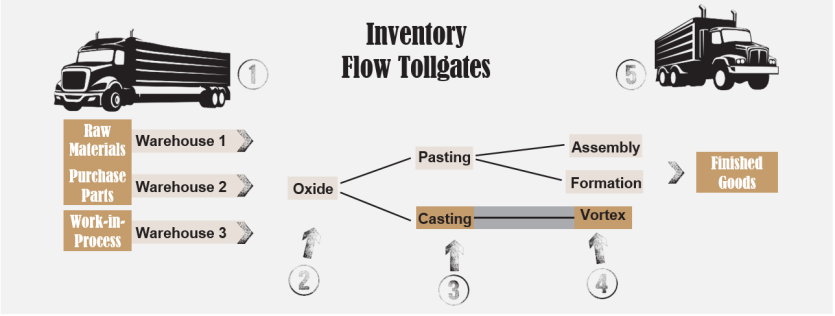

Monitoring of the five tollgates of inventory movement is critical for materials management and the desire for an annual physical inventory that results in minimal financial write-off. The tollgates include 1) Receipt of Material, 2) Internal Failure, 3) Production Reporting, 4) Bill of Material (BOM) Accuracy, and 5) Shipping. These five checkpoints are validated at fiscal year-end by a periodic physical inventory.

1. Receipt of Material

Inventory verification is not limited to cycle counts of the various raw materials, purchased parts, work-in-process (WIP) and finished goods (FG) but includes the validation of these various inventory types on the receiving docks. As an example, it is a daily routine that nearly 30 truckloads of lead (Pb) are delivered with various alloys and receiving tickets specifying the pounds and unique part numbers. One of the EICE checklist verifications calls for the dock workers to document the physical weighing of all “pigs” (60 pounds) and “hogs” (2,000 pounds) of each alloy type each day (pigs and hogs were smelter terms given to designate these blocks of Pb). These pigs and hogs, when cast by the supplier, might vary from 55-65 pounds or 1,900-2,100 pounds respectively, depending on the rounding on the top of the mold and the amount of dross. The controller’s job is to ascertain these weights are being performed daily and are compared to what was entered into the Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP)2 software. Obviously, receiving 2,000 pounds of a product onto the books when physically 1,900 pounds is taken into possession will result in an overpayment and an eventual inventory loss.

Other inventory-related checkpoints are spare parts used in the repair and maintenance of production equipment. Although not listed on the balance sheet as inventory per se, the expectation from SOX as implemented by Exide is to control materials within a facility. Exide uses a software platform to manage spare parts within a caged controlled area and maintains inventory levels to ensure parts are available to service equipment. Exide holds about $1 million in spare parts at this facility, all of which are expensed when purchased and received. The threshold of materiality is not met, allowing immediate expense rather than capitalization of the cost until used. SOX regulations, as interpreted by Exide’s internal and external auditors, expect monthly cycle counts to establish that spare parts inventory is being managed and controlled, indirectly proving that the operating budget and forecasts are being adhered to and promoting confidence that the product’s various raw material, WIP and FG inventory accounts are being monitored daily.

2. Internal Failure

This rather disconcerting phrase is commonly referred to as “scrap” in manufacturing environments. Also called “nonconforming product,” scrap is a normal outflow of processes that are inherently flawed. A nominal amount of scrap is expected from destructive testing, but non-destructive scrap is a significant aspect of plant management. Six Sigma3 is a study of process variation and seeks to align company goals with shop floor operations in continually reducing scrap and increasing the velocity of output through a pull system of inventory. Statistical process control (SPC)4 drives much of the methodology today, and accounting professionals play a major role in providing data and understanding of the causal effects of production and scrap on the financial statements. The escalating costs of quality become most challenging as the dollars snowball into “failure.” Internal failure is directly related to inventory on the balance sheet, as external failure is the other side of “failure” resulting from warranty claims and potential liability issues outside of a facility’s four walls. Warranty claims may require replacement of the product, a cash refund or significant future costs like contingent liabilities for demurrage, legal fees, and medical costs for harm inflicted on customers. But this potential liability for external failure is irrelevant to the inventory balance carried as an asset on the balance sheet.

A daily primary responsibility of the site controller is to walk the plant floor every morning to see what the current issues are and the potential impact on the weekly financial forecast. Inventory stacked up between WIP centers, extraordinary unprocessed scrap, operators standing idle and equipment being repaired are a few of the issues to be investigated by the accounting function. American manufacturing companies have adopted a concept called Gemba,5 where management must go to “the real place” to understand the issues, opportunities and constraints facing the workers. The evolving role of accounting professionals, and particularly management accountants, requires an understanding of their businesses, and leadership is required not just in the office but also on the production and distribution floors. Exide was an Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM)6 for Toyota, among others, and much of the Toyota Production System (TPS)7 was implemented to serve the customer. Japanese concepts such as jidoka, poka-yoke, 5S and takt time8 focus on quality improvements and efficient production.

3. Production Reporting

Another important objective of the Gemba walks is to observe the production reporting processes that result in the creation of the next-level WIP with reduction of lower-level WIP. Each successive production level adds direct materials, direct labor and overhead in the defined BOM and labor routings. Exide uses direct labor as the cost driver to allocate the overhead pool based on industrial engineering time/motion studies. Experience associated with Exide’s past practice as a production-driven company proves a tendency to over-report quantities manufactured or assembled in order to meet the required corporate schedules.9 Each pallet of production generates a barcode label with the part number and quantity, thereby relieving the subparts used in this particular product. If a barcode is generated in error or intentionally without physical production taking place, that ghost pallet would eventually be determined as nonexistent and deleted. The corresponding subparts display as a negative on the costed stock status and result in a gain. The netting of the loss from the nonexistent barcode and the gain from subparts would be an overall loss due to the conversion costs of direct labor and overhead being applied in error by the ERP system. As detailed previously in the internal failure tollgate, the snowball effect of adding layers of cost in each successive WIP center will become a loss at some point when production quantities are overstated.

Cycle counters are employed 24/7 in both manufacturing and distribution sides of the operation to maintain control of the location of inventory produced. The unique barcodes have a unique warehouse bin location where material handlers “pick and put” these pallets in appropriate locations that number over 15,000 bins. The role of the cycle counters is to continuously check the bin locations with the product located there with use of radio frequency identification (RFID)10 scanners. Part of the SOX 404 EICE quarterly checklist is reporting and signing of barcodes that would be “killed” due to errors in production reporting. In order to maintain independence of the audit by these counters from production reporting, cycle counters report administratively to the materials manager. In addition, these counters report functionally to the inventory accountant and controller for resolution of reporting issues in production and also internal failure.

4. Bill of Material Accuracy

Tollgate four is a frequently overlooked facet of manufacturing control because if it’s in the ERP software, it must be right. Seriously, though, ongoing verification of the bills of material for each manufactured product with shop floor reality is crucial for managing inventory and the potential for loss (or gains). Competing objectives from the quality assurance (QA) function’s material usage ranges and cost accounting standards (one point, no range) add to the potential for inventory losses. Suppose the QA standard allows for 2.4-2.6 pounds of Pb to be used for a battery strap that connects the inner plates. The BOM pounds designated is 2.5 and is used for costing the product and in generating the purchase orders based on this standard usage. QA may routinely check the mold setup and, in conjunction with shop floor operators, cast the strap at the high end of the range because of a belief that more is better in making a stronger strap. Casting to a 2.6-pound strap would result in a 0.1-pound loss for every battery produced in that mold setup. Perhaps a newer mold is installed with engineered cavities to require less lead per strap with the same quality. This could result in a typical 2.4-pound setup and a 0.1-pound gain per battery produced on that line. Imagine, 30,000 batteries built in one day could result in a 3,000-pound loss or gain, which translates to more than $1,000 to the bottom line. The potential for an inventory shortage of a certain item could have severe consequences for the operation’s uptime. Stocking out would result in idle labor, scrap and extra shifts at an overtime premium.

An additional facet indirectly related to BOM is the common use of substitutions for orders. If sufficient quantities of Cold Cranking Amps (CCA) for a certain Battery Council International (BCI) Group Size11 are not available but a larger one is, there is a cost to be incurred. Suppose the CCA12 ordered is 525, but only a 600 is in stock, and the cost differential is $1.50. Fulfillment of the order, at the same sales price, will result in a substitution loss. If this substitution transaction goes unreported, then an inventory loss will occur by the cycle counter or, if missed, at the annual physical inventory. Inventory errors are self-correcting. A miscount or omission in one period is typically adjusted accurately in the next count.

5. Shipping Verification

The final tollgate is a major threshold where fully priced inventory stock must be controlled as customers’ performance obligations are met. The transfer of ownership may occur at the facility’s docks or at delivery to the customers’ warehouses and would impact revenue recognition, but that is another topic for another day. The essence of this fifth tollgate is movement from inventory to cost of goods sold (COGS) and recording of sales revenue with accounts receivable. Exide typically has 125,000 orders open (individual batteries to be shipped) at any given time, with many of those orders days out. The fulfillment of an order is very structured, with material handlers “picking” from warehouse inventory bin locations the various types and quantities for labeling and preparation on a distribution line. Once a shipment is assembled, the pallets are “ship confirmed” in the ERP system, thereby crediting inventory and debiting cost of goods sold. The corresponding debit to the customer’s accounts receivable and credit to sale revenue would complete the transaction. Once all pallets are loaded on a truck, the door is sealed with a tag number, and the information would be communicated to the security guardhouse. A final check is made by the guard, including their approval that the seal is in place. The physical custody of inventory at this stage is crucial, as an asset value snowballs through the various WIPs to finished goods. This final tollgate, as the asset leaves the balance sheet, ensures the security of full-costed material movement to the customer.

The Role of the Annual Physical Inventory

To ensure the operating responsibilities are being adhered to at each of the five tollgates, an annual physical inventory is conducted to verify the accuracy of the perpetual system and the manual inputs that standard work instructions drive in the day-to-day operations. Paramount to all companies is that written policies and procedures in effect must be followed with an end-of-year physical inventory validating the processes and tollgates of control. Witness to the importance of this annual count are officials from internal audit, external auditors, and supervision by the site controller. Materials planning and production personnel are excluded from the oversight due to potential conflicts of interest in the outcomes.

Assurance that proper receiving and shipping cutoffs are followed and production/scrap reporting is completed prior to an inventory freeze on the books may be likened to slowing the flow of a stream. It is easiest to cross a stream when the water is down, and that is similar to the time that a physical inventory is conducted. Many firms seek to have this periodic count coincide with fiscal year-end to facilitate the recording and reporting processes for inventory. Companies elect a year-end at a slow time for sales to facilitate year-end closings that will reduce the opportunity for errors. With expedited closing schedules, the probability of mistakes increases, impacting the financial statements. Exide’s fiscal year-end was March 31 due to the slowest time of year for battery demand and shipments. The annual physical was normally in late January, but in recent years was moved to the third weekend of March. Stopping the flow of the inventory stream at this time of the year is easier, although still a complex event that requires much advanced planning and three days to prepare, count and record the stock levels on hand.

Inventory is typically in the $20 million range, and with an average turnover at 12 times, one can see the impact of the count is verification of $240 million in COGS that flowed through the facility. Even the $20 million on hand was questioned by both audit teams as to the presence of slow-moving or obsolete product on hand in inventory. To reduce the risk of intentionally not writing inventory down in the normal course of business, the Exide corporate office sought to encourage the timely write-down of inventory to saleable or recyclable values by instituting a Material Request Disposal Authorization (MRDA) process that enabled plants to write down product that was overproduced or unsold due to corporate build schedules. These scrap dollars are reclassified from the plant to the division level at the corporate office since they are responsible for the over-production or reduced customer demand. Blemished batteries are also sold for 50% off the normal cost, and this further encourages plants to do the right thing and not harbor scrap on the books at full value.

The primary problem is defining what a significant inventory variance is in dollars or as a percentage of total inventory value and what course of action is followed by corporate officials and external auditors when these thresholds are exceeded. The importance of the issue is that the outcome from a physical inventory count is a key measure of control of a corporation’s operational processes. An acceptable inventory loss indicates all tollgates are collectively accurate and ensures financial reporting is without material weakness. Gaining an understanding of corporate governance in valuation of assets, and particularly inventory, is a significant area of interest for the financial leadership of manufacturing companies. Exide uses an ERP system with integrated financial software supporting materials planning, production reporting, costing, distribution and financial reporting. The reporting is real-time, including the movement of inventory throughout the facility. Knowledge gained from these ongoing write-downs provides improved estimates for contra allowance accounts for net realizable values and provides corporate leaders with necessary insight on what policies and procedures are in place when annual physical inventory losses exceed the allowance set aside.

Summary

Once an annual inventory is complete, a drill down into the data on the gains and losses by category and part number will reveal where further investigations are needed:

- Is cycle counting a robust process that adds value and not just cost to the facility?

- Are the cycle counters covering all bin locations in a systematic manner?

- Are BOMs accurate for all alloys and production WIP?

- Are there significant losses of certain types of inventory and gains in others?

- Is the receiving dock following standard work instructions?

- Is production reporting accurate? Losses in a specific WIP item type with associated gains upstream point to over-reported production.

- Is budgeting for prevention and appraisal costs sufficient to mitigate internal and external failure costs?

- Does the guardhouse perform the final check consistently and raise concern when issues arise?

- Is there a culture of following policies, procedures and work instructions daily?

- Are workers comfortable in bringing issues to supervisors or staff?

- Is a third-party 1-800 fraud line needed for employees to address their concerns?

McNally13 emphasizes that COSO’s key concepts pertaining to internal control are enduring. The 2013 Framework still provides for three categories of objectives – operations, reporting and compliance – and focuses on five components of internal control – control environment, risk assessment, control activities, information and communication, and monitoring activities. Management accountants and controllers at the manufacturing and distribution level must be the leaders for operational and financial control. But it requires more than just technical expertise in accounting. Ethical leadership to do the right thing is a must, while developing relational skills to interact with various personalities is critical to personal and organizational success. Understanding the industry in which you compete and the COSO Framework is essential in establishing tollgates of control to ensure all stakeholders can rely on the financial statements.

About the Author

Dr. Faidley has more than 33 years of experience in corporate, manufacturing and supply chain accounting and financial leadership. His experience extends to work with defense contractors and not-for-profit firms as well. He has been employed with East Tennessee State University for 10 years, serving as chair of accountancy since 2020.

References

1 Sarbanes Oxley. SOX Section 404: Management Assessment of Internal Controls. https://bit.ly/soxsec404

2 SAP. What is ERP? https://bit.ly/saperp

3 American Society for Quality. What is Six Sigma? https://bit.ly/asqsixsigma

4 Hessing, T. Statistical Process Control (SPC). https://bit.ly/ hessingsigma

5 Lean Enterprise Institute. Gemba. https://bit.ly/leangemba

6 Corporate Finance Institute. Original Equipment Manufacturer: What is an Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM)? https://bit.ly/cfioem

7 Toyota. Toyota Production System. https://bit.ly/toyotaprod

8 Quality Gurus. Glossary of Japanese Lean Terms. https://bit.ly/ qualitylean

9 Einhorn, C.S. (1996, June 17). Numbers Game. Baron’s, 76(25), 36.

10 Camcode. Using RFID for Inventory Management: Pros and Cons. https://bit.ly/camcoderfid

11 Battery Group Size. How to Choose Your Battery. https://bit.ly/choosebattery

12 Walker, D. (2022). What Does A CCA Battery Ratings Mean? https://bit.ly/ccaratings

13 McNally, J. S. (2013). The 2013 COSO Framework & SOX

This article was originally published in the November/December 2024 Tennessee CPA Journal.